Nimisha Priya, barely 19, left the southern Indian state of Kerala for Yemen in 2008 with big dreams.

She had found work as a nurse in a government-run hospital in the capital Saan’a and told her mother, a poorly-paid domestic helper, that their days of hardships would be over soon.

Fifteen years later, that dream has turned into a nightmare for Nimisha and her family. The 34-year-old is on death row for murdering a local man, Talal Abdo Madhi. She’s counting out her days in Sana’a central jail in the capital of the war-torn country.

On 13 November, Yemen’s Supreme Judicial Council rejected her appeal, clearing the decks for her execution. But as Yemen follows Sharia law, the court gave her one last option of escaping death – she can secure a pardon from the victim’s family by paying diyah or “blood money”. Now, her family and campaigners are racing against time, hoping to pull a miracle and get that pardon that would allow her to live.

‘Take my life instead’

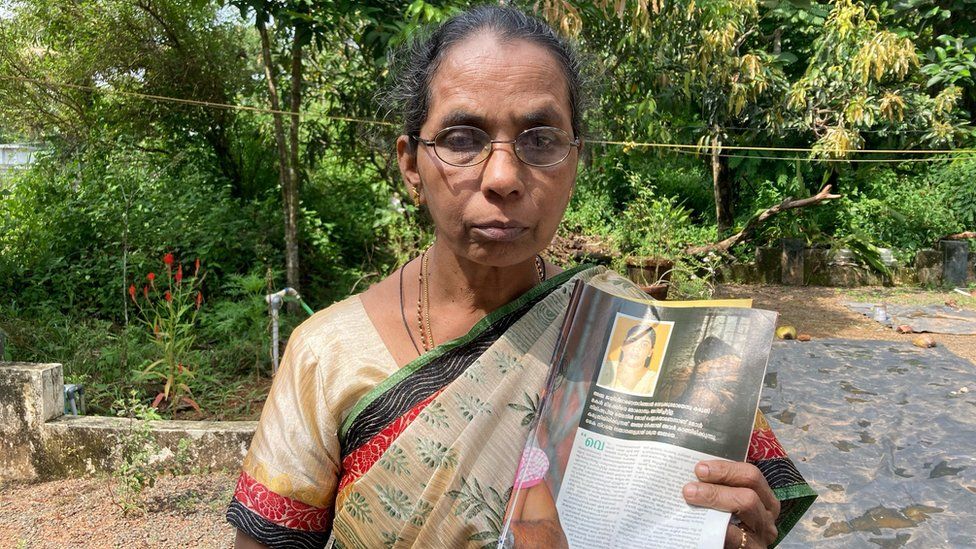

Prema Kumari, Nimisha’s 57-year-old mother, breaks down repeatedly as she describes her daughter’s ordeal.

“I will go to Yemen and seek their forgiveness. I will apologise to them, I’ll tell them, take my life but please spare my daughter,” says Prema Kumari who lives in the southern Indian city of Kochi. “Nimisha has a young daughter who needs her mother.”

But travelling to Yemen is not easy. A 2017 Indian government ban on citizens travelling to Yemen remains and those needing to travel need special permission.

A lobby group called Save Nimisha Priya International Action Council has filed a petition in the Delhi high court, seeking permission for Nimisha’s mother and her 11-year-old daughter Mishal to travel to Sana’a. It said two council members would accompany them.

But last Friday, Indian authorities rejected the request, saying they didn’t have a diplomatic presence in Yemen to ensure their safety.

The government’s assessment is based on the political condition in Yemen. Saan’a is controlled by Houthi rebels who have been locked in a prolonged civil war with Yemen’s official government , which is based in-exile in Saudi Arabia. India does not recognise Houthis so a trip to Yemen for Indian citizens is bound to be fraught with dangers – they will have to fly to Aden and then travel for 12-14 hours to Sana’a by road.

The Save Nimisha council has once again approached the Delhi high court, renewing its request to allow her mother and daughter to travel to Yemen. And with each passing day, Prema Kumari’s desperation is growing. “I don’t want my daughter to die in a foreign land,” she says.

“What happened to Nimisha is very unfortunate, she doesn’t deserve it,” says Babu John, social activist and member of the Save Nimisha council. He adds that Nimisha was looking at a bright future but got stranded in Yemen when the civil war broke out.

Nimisha, her mother says, was good at studies and the local church supported her school education and paid for her nursing diploma course. But she was ineligible for a nursing job in Kerala because she hadn’t cleared her school leaving exams before doing the diploma.

The job in Yemen was meant to be her ticket out of crippling poverty.

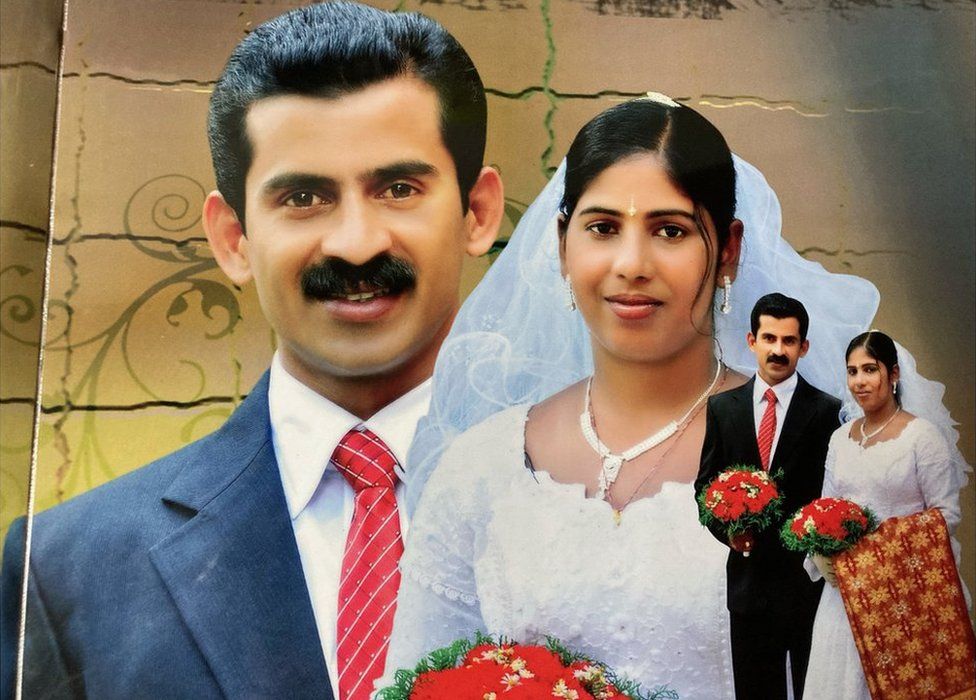

In 2011, she returned home to marry Tomy Thomas in a match arranged by her family. The couple returned to Yemen, where he found work as an electrician’s assistant, but the pay was paltry. After December 2012, when their daughter was born, they struggled to make a living and in 2014, Thomas returned along with the child to Kochi where he now drives a tuk-tuk.

Nimisha decided to quit her low-paying job and start her own clinic in 2014. But the law in Yemen mandated her to have a local as a partner and that’s where Mahdi came into the picture. He ran a textile store nearby and his wife had given birth in the clinic where Nimisha worked. In January 2015, when Nimisha came home for her daughter’s baptism, Mahdi came along for a holiday.

Nimisha and her husband borrowed money from friends and family, together raising 5m rupees ($60,000; £47,000), and a month later, Nimisha returned to Yemen to start her clinic. She also started the paperwork so her husband and daughter could join her in Yemen, but in March, a civil war broke out there and they couldn’t travel.

Over the next two months, India evacuated 4,600 citizens and nearly 1,000 foreign nationals from Yemen. Nimisha was among a few hundreds who did not leave. “We had invested so much money in the clinic and she couldn’t just get up and leave,” Thomas says.

On his phone, he shows me photographs of the 14-bed clinic – the signboard of the Al Aman Medical Clinic, spanking new blue chairs in the reception area, a man in a white coat posing next to brand new lab equipment, a new Sony TV mounted on a wall in the waiting room, and Mahdi sitting in the pharmacy.

The clinic, Thomas says, soon started doing well, but Nimisha also started to complain about Mahdi.

According to the petition in the Delhi high court – which the BBC has seen – Mahdi “stole a photograph of Nimisha’s wedding when he visited their home in Kochi and he later manipulated it to claim he was married to Nimisha”.

It says that “he physically tortured her and took away all the revenue collection from the clinic” and that their “relationship deteriorated when Nimisha questioned him about embezzlement of funds”.

On several occasions, “he threatened her with a gun” and “seized her passport to prevent her from leaving”. And when she complained to the police, “instead of taking any action against him, they locked her up for six days”, it adds.

The murder – and the arrest

Thomas first learnt about the murder in 2017 through TV news channels.

“The headline was – Malayali [Kerala] nurse Nimisha Priya arrested for murdering husband, chopping up his body in Yemen,” he says. Nimisha was arrested from close to Yemen’s border with Saudi Arabia – more than a month after Mahdi’s chopped up body was found in a water tank.

“How could this man be her husband when she was married to me?” he asks while showing me their wedding album.

Tomy Thomas says when she called him from prison a few days after her arrest, they both cried. “She said she had done all this for me and our child. She could have taken the easy way and lived with Mahdi, but she didn’t want to do that. My love and affection for her has grown after this ordeal.”

KR Subhash Chandran, a migrant rights activist and Supreme Court lawyer who is representing Nimisha’s mother and the council in the Delhi high court, says “Nimisha did not really intend to kill Mahdi” and that “she too is a victim”.

“Mahdi had confiscated her passport and she was trying to get it back from him. So, she tried to sedate him, but she overdosed him and he died,” he says.

The exploitation of semi-skilled and unskilled Indian workers in Gulf countries is well documented. Activists say many countries in the region practice Kafala – which means the employer keeps a worker’s passport and documents. International Labour Organization says it’s slavery by another name and opens migrant works to all sorts of abuse.

Most victims of Kafala, Chandran says, are Indian women who go to the Middle East to work as domestic workers, trying to escape poverty at home.

He is now also calling for “a retrial so Nimisha has a chance to defend herself”.

“She did not receive a proper legal trial. The court appointed a junior lawyer to represent her but she couldn’t communicate with him because she doesn’t know any Arabic. She wasn’t given an interpreter and she had no idea what documents she was signing,” he says.

Yemeni authorities have not commented on the case in Delhi.

Deepa Joseph, lawyer and social activist and vice-chair of the Save Nimisha council, says the Indian government’s support is key to saving Nimisha. “The only option is to seek forgiveness from Mahdi’s family and negotiate blood money with them.”

A well-known business tycoon from Kerala has already pledged 10m rupees ($112,000 ;£95,000) to the cause. And the council is confident that Kerala residents at home and in the diaspora would contribute to make up any shortfall.

“I have full hope that Nimisha can be saved. I think the victim’s family will accept the blood money,” Ms Joseph says. “She may have committed a serious crime but I want to save her for her mother and her daughter.”

Prema Kumari is now hoping to travel to Yemen and speak to Mahdi’s family.

When Mr Thomas spoke to his wife just days before Yemen’s Supreme Council rejected her appeal, Nimisha sounded hopeful. “Keep your strength and pray for me,” she’d told him. But when he spoke to her after the court decision, she sounded “depressed”.

“I tried to console her by saying that efforts were being made to save her life, but she didn’t sound convinced. How can I remain hopeful? she asked me,” he said.

(BBC)