South Korea’s government has ordered more than 1,000 junior doctors to return to work after many staged walk-outs in protest of plans to increase the number of doctors in the system.

More than 6,000 interns and residents had resigned on Monday, said officials.

South Korea has one of the lowest doctor-per-patient ratios among OECD countries so the government wants to add more medical school placements. But doctors oppose the prospect of greater competition, observers say.

South Korea has a highly privatised healthcare system where most procedures are tied to insurance payments, and more than 90% of hospitals are private.

Its doctors are among the best-paid in the world, with 2022 OECD data showing the average specialist at a public hospital receives nearly $200,000 (£159,000) a year; a salary far exceeding the national average pay.

But there are currently only 2.5 doctors per 1,000 people – the second lowest rate in the OECD group of nations after Mexico. “More doctors mean more competition and reduced income for them, that is why they are against the proposal to increase physician supply,” said Prof Soonman Kwon, a public health expert at Seoul National University.

Patients and health officials expressed concerns on Tuesday as reports emerged of doctors declining to come into hospitals across the country.

Junior doctors form a core contingent of staff in emergency wards, and local media reported that up to 37% of doctors could be affected at the biggest hospitals in Seoul.

The health ministry said 1,630 doctors had not shown up to work on Monday, amid a wider group of 6,415 who had submitted resignation letters. Organisers had pledged an all-out strike from Tuesday.

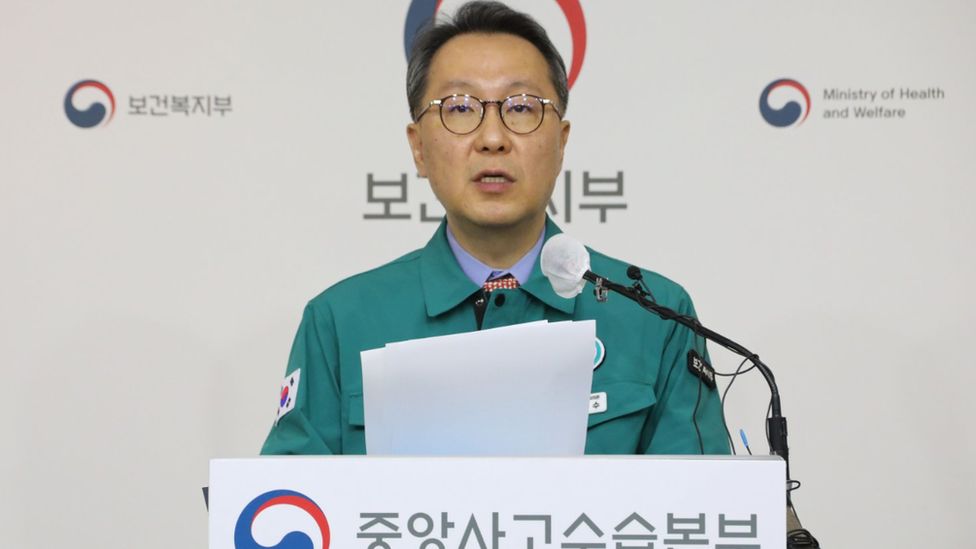

“We are deeply disappointed in the situation where trainee doctors are refusing to work,” Second Vice Health Minister Park Min-soo had told reporters earlier this week. He also warned that the government may resort to legal means to get doctors back to work.

Under the country’s Medical Services Act, authorities have the power to revoke a doctor’s practicing licence over an extended labour action which threatens the health care system. The country has attempted prosecutions before in relation to other doctor protests- which were later dropped.

“We earnestly ask the doctors to withdraw their decision to resign en masse,” Mr Park said.

The government has consistently condemned the doctors’ opposition. Prime Minister Han Duck-soo has said: “This is something that takes the lives and health of the people hostage”.

The extent of the strike’s impact so far is yet unclear, although officials had warned there could be delays to surgeries and gaps in care. Some hospitals have announced switching to contingency plans. The government has also fully expanded telehealth services.

The protests are similar to events in 2020, when up to 80% of junior doctors joined strikes against the government’s recruitment plans.

South Korean policy makers have tried for years to increase the number of trained doctors, as the country is dealing with a rapidly-ageing population which will put extra burden on the medical system. There’s a projected shortfall of 15,000 doctors by 2035.

The country also has critical gaps in care in remote areas, and in specialities such as paediatrics and obstetrics – which are seen as less lucrative fields compared to dermatology.

To combat this, President Yoon Suk-yeol has proposed adding 2,000 spots per year to medical schools – which currently take a cohort of just over 3,000 students every year – a rate that has not changed since 2006. It’s a policy very popular with the public – with local polls showing 70-80% of voters support it.

However the plan has been strongly opposed by the medical profession, with groups like the Korean Medical Association arguing an increase would be a strain on the money available under the national health insurance scheme.

The union has also argued that more doctors wouldn’t necessarily address the shortages in specific fields. It announced the strike action on Sunday after an emergency meeting with hospital representatives. While junior doctors are the first to strike there are fears that more across the profession will join too.

Doctors successfully staved off the government’s previous attempt to introduce more graduates in 2020. The government conceded at the time, partly due to the pressure of the Covid pandemic, commentators say.

“It is not easy to predict who will win this time,” said Prof Kwon. He noted that President Yoon “seems very determined” because the policy has provided a ratings-bump for an unpopular leader otherwise tarnished by some political scandals. “But a private sector dominated health system is quite vulnerable to physician strikes, i.e. it can be really shut down if doctors join full-scale strikes.”

(BBC)